20 Years Unlearning to Garden

In 1986 I experienced a watershed event. I dragged my wife, and kids of 4 and 2 years, to the Second North American Bioregional Congress in Wisconsin. I thought I could contribute to making the world a better place for the generations to come. What I discovered is that no one attending had any idea how the existing system works (including me) . . . let alone offering a practical idea of how to make it work better.

I decided then that I would take five years, earn enough money to pursue the ideas I wanted to pursue, and figure this stuff out. It took me eighteen years for the 'earn enough money' part. As I said, I must be a slow learner.

To share this technique I started a business called Organic Landscape Design and began promoting this no-till way of gardening. That led to an agreement with David Ward of Nice-World who was interested in building community gardens. Our first joint effort in 2009 was at a church in Broomfield. I developed a poster explaining what we were doing and used it in talks to any group that would listen.

By 2011 David and I had 7 community gardens in the metro area. As far as I know there are two still active, one at the Grange in Broomfield and one at Regis University. These gardens were built with hay and manure according to the directions documented in Toby Hemenway's 'Gaia's Garden'.

In 2011 I did an experiment to test Leo's results. The experiment was a round bed in my Mother's front yard. We used hay on 1/3, wood chips on 1/3, and a mix of sticks and wood chips on 1/3. The plants did just fine in all three sections. However, the hay in the hay sections was all used up in that first year. The wood chip section lasted four years. I planted the sticks and wood chip section for 6 years before I added more material.

As you see from the diagram above, we are using about 3 inches of manure for 12 inches of organic matter. As far as the plants are concerned, it does not seem to matter whether we are using hay, wood chips, or logs (except we need wood chips on top of logs to root the seeds). What does seem to make a difference is the freshness of the manure. The only failed sheet mulches I have ever built were built with old (aged) manure.

It is a gardening truism that we cannot use fresh manures because those contain too much nitrogen and that will burn your plants. Yet, here I was using raw wood and fresh manure and my plants had plenty of nitrogen and were not burned. Clearly we had a lot to learn about the relationships between plants and soils.

________________

My goal throughout this process has been to share an idea. I wanted to share the idea that it is possible to 'heal nature and produce abundance' if we understand that we are 'already a part of a community that consists of all the living things around us and that our individual well being cannot be separated from the well being of that community'. To heal nature we stop doing those things that break apart natural relationships and facilitate the regeneration of the missing connections.

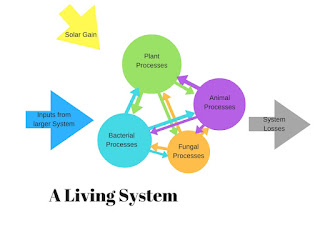

To further that goal, I have been experimenting with what we call 'integrated systems of production' combining our gardens with our greenhouse and our chicken flock, bees, pollinator plantings, hay field, and natural areas. By placing these processes in proximity we increase the amount of carbon (in the form of organic molecules) cycling through our system and build up resources in the system cycle over cycle. Our deep mulch polycultures are the most obvious result of that experimentation but the ultimate pattern we seek is much more inclusive than that.

In order to share this information I have tried everything I could think of:

- Meet Up Group - I took over the Greater Denver Urban Homesteading Meet Up Group, maybe 12 years ago, and asked everyone doing these kinds of project to post their events there. I also posted the events I was holding and over the years we built up membership in the meetup group to (at the time of this writing) 4,363 urban homesteaders.

- E-Mail List - I annually held a series of events about deep mulch gardening, greenhouses, chickens, and scything. At the events I held, I let people sign up for our newsletter and over the years have acquired over 500 subscribers.

- Internships - Every year I have had at least one intern and sometimes as many as 6 working with me at any one time. You can see some of their testimonials on the web site.

- Green House - In 2012 we built a green house attached to the south side of my mother's house. It is intended as a demonstration of an inexpensive structure, that can be attached to the south side of any building, and produce fresh greens and protein year round. We continue to experiment with it.

- Seed Saving and Chicken Breeding - I have been saving seeds from certain tomatoes since 2009 and have also saved seeds from a variety of pie pumpkin. I have experiments with saving carrot seeds and we let other plants, such as lettuce and pole beans reseed themselves. We started our chicken flock, and started raising our own chicks in 2011. A lot more could be done if we could coordinate these activities as a community.

- Bee Hive Builds - We held bee hive builds. We bought some sheets of plywood and invited budding beekeepers to contribute $100 and participate in building their own hives. This was a popular event, however, our lead beekeeper decided that purchased boxes were better for his business and we stopped holding this event after three successful years.

- Plant Sales - A couple of springs we invited people to bring the plants they were growing to a plant sale. We had fun but there is a lot of competition for plant sales in May and I didn't know how to make ours distinctive.

- Community Organizing - Applying carbon cycling technologies is best accomplished at the scale of neighborhood and over the years I have promoted a number of ideas to facilitate that. We had the community gardens, we had the API gardening team, we had a workshop called "Principles of Community Design", we set up the High Plains Plant Propagation Cooperative which has now evolved into the "Neighborhood Nursery Project", and we had our most successful project called Bee Safe Neighborhoods.

- Bee Safe Neighborhoods - Through the Bee Safe Neighborhood projects we signed up 74 different neighborhood coordinators around the country and into Canada. Of those, 6 neighborhoods and 3 organizations were successful at signing up 75 contiguous neighbors to pledge to abstain from systemic poisons. See the Coordinator List and the Honor Roll. We never had the resources to promote the Bee Safe Neighborhoods ourselves. For a while a group in Boulder was doing it and at one time the People and Pollinators Action Network expressed interest. The program was also adopted by the City of Lakewood as a part of its Sustainable Neighborhood Program. You may have seen the signs around.

- Reinhabit Cooperative - Originally known as the Cook and Gardener Project, the Reinhabit Cooperative teaches carbon cycling techniques to people looking to build a career as gardeners who will work with homeowners to create thriving habitats on their properties. Since the year 2020 we have engaged 30+ homeowners hiring 13 different gardeners. In 2022 our gardeners earned $8,430 through LSI plus what they billed directly. In 2023 that number rose to $13,188. In the long term, if successful, this project will produce an abundance of food and we intend to begin the 'Cook' part of the project.

- Cook What You Grow - In anticipation of starting the cook part of 'The Cook and the Gardener' I wrote a cook book. It is a book about the biggest problems we humans face on this planet. Those problems can be traced to our relationships with the smallest of organisms. Part cookbook, part history lesson, part healthy living guide, this short work shows us a pathway to a positive future.

- Web Site - I have also done a lot of social media networking (mostly on Face Book) trying to refine the language we use to convey the message. The results of that effort are shown on the web site we redeveloped in 2021 to make it functional on mobile devises. In addition to documenting the programs discussed above, there are numerous works about the power of individuals and communities to create the kind of world we would wish for our grandchildren. In that regard, I am most proud of Agents of Habitat.

- Agents of Habitat - This is a series of 12 lessons about individuals taking the future of the world into their own hands. I have taken things about as far as I can. We are in process of transferring responsibility for the Living Systems Institute to a new generation. One of the most important tasks they have is to take the lessons of Agents of Habitat and make them more accessible for the generations that follow. What we have accomplished to date was done without substantial funding and was only possible because I did not need a salary. We are no longer able to run an all volunteer organization. If this work is to proceed we will need to pay those who dedicate their time to a brighter future.

________________________

The problem with running 7 different community gardens is that there is no way to control how much a member of the community absorbs when I present these ideas. Everyone comes with some understanding about gardening that differs from what I was teaching and that other understanding was always liable to express itself.

I called what we were doing a No Weed, No Water, No Till, Deep Mulch, Drip Irrigated Gardening System. The no weed part is what is hardest for people. There are plants that will grow up and want to take the light we want for our crops. These plants are not weeds, they are potential mulch. They are not rooted in the soil but rather the mulch so they are easy to pull. The longer we wait to pull them the more mulch they are. When the volunteers begin to take the light from our crops we pull these volunteer plants and lay them down right where they grew. Because we have a healthy soil ecosystem those plants are quickly cycled through fungi and bacteria and back to our plants.

I would give my presentation at the beginning of the gardening season and then tour the gardens throughout the season. Consistently I would find piles of organic matter pulled out of the gardens and wasted. Or, the alternative, new gardeners could not tell the difference between the crops they were growing and the volunteers and the volunteers were outgrowing the crops. Either way, a partial understanding of the process does not work well.

It is also true that Organic Landscape Design was not making any money. As a result I decided that I would make people come and see my gardens and offer to teach them the right way to do things. I started the Applewood Permaculture Institute (API) and set about demonstrating how a neighborhood gardening team might work.

The API gardening team grew over a year or two to some 20 members spread over the west metro area. As a team, we built deep mulch gardens for everyone who wanted one, built chicken coops for everyone who wanted one, and built bee hives for everyone who wanted one. But, we were not tied to a neighborhood and the active members became spread too thin. I asked the team members to follow up in their own neighborhoods but as far as I know, there are no active neighborhood gardening teams doing what we were doing.

It was during this time that I decided to go ahead and set up a non-profit organization. The Living Systems Institute (LSI) was granted its tax exempt status as of January 2013. LSI continued the work of the preceding organizations but, even as a non-profit we have been unable to attract funding. Hopefully, this new generation taking over, will be able to design projects attractive to funders. It is clear that my learning was much too slow for that.

All of that brings me to the most important of the erroneous assumptions that prevent us from creating the world we want. Our culture believes that there is a struggle between good and evil. But there is no such thing as good and bad in a complex adaptive system. The system is what it is. It is a pattern of interactions among those living organisms that can survive in the pattern. We can influence the pattern toward more diversity or less diversity. A diverse pattern of interactions builds resources into itself cycle over cycle. A monoculture, where the competition is eradicated, requires constant inputs from outside. At the level of the living system on this planet, the only available inputs are those resources stored up from before.

We are beginning to learn the science of that for plants in a garden. The plants exude sugars into the soil to attract fungi and bacteria. In exchange for the sugars the bacteria provide usable nitrogen and the fungi bring water and minerals. In an organic monoculture that system can work at a low level. When we companion plant and use volunteers as mulch, the system will experience what biologists call quorum sensing. Quorum sensing is a significant increase in biological activity in the soil that occurs when a certain diversity of plants is reached.

In essence, the plants in a natural setting cooperate underground with the soil organisms to create a thriving pattern of interactions. Above ground they compete for light but we can intervene to achieve both food for ourselves and a thriving soil ecosystem. We intervene in the way that our ancestors and other animals have always adjusted the pattern of plants in the system. This same lesson applies to the pattern of interactions that make up our communities.

I wish I had learned fast enough to experience a thriving community based on understanding this principle of cooperation among diverse elements of a system. And while there are many organizations working on various aspects of the problems facing our species, I know of none besides the Living Systems Institute that is researching, designing, and testing the whole pattern of interactions at the scale that directly affects individual organisms. That is the scale of soils and neighborhoods. I would think that our culture would want to fund that work.

Comments

Post a Comment